@Bindings

In his post about Bindings, the delightful Chris Eidhof gives an overview about how synthesizing SwiftUI Bindings might not turn out how you expect. The tl;dr is using Binding(get:set:) might be convenient, but can introduce performance bottlenecks, especially in complex views or when creating member bindings. Chris recommends against using this in production code.

As someone who has used a Binding(get:set:) in production, I wanted to investigate a little further as well as give a little backstory as to why you’d want to use Binding(get:set:) in the first place.

SwiftUI Alert

I’m going to use SwiftUI Alert as an example but there are other instances in SwiftUI where the view modifier that dictates whether something is to be shown takes a Binding<Bool>. It will this Binding get determines whether it will be shown and the set gets called when the alert is no longer shown.

The result is that you might have a @State var shouldShowAlert: Bool = false declared at the top of your view and you’re ready to go! Very few apps are simply there to show an alert. In fact, a determination to show an alert is usually dependent on a condition or state change with actual real data, e.g., a response object came back as nil. This means that you’ll probably have logic in your view that controls flipping your shouldShowAlert bool based on certain conditions. If you’ve been around, you might have read “logic in your view” and replaced it in your mind with “logic in your view that is not easily unit tested”.

So, you might write something like:

Binding(get: { return yourObject == nil },

set: { if $0 { resetState() } } )

When In Doubt, Measure

Fortunately, we have a tool at our disposal that might give some clarity as to whether it’s as bad as we suspect: Good Ol’ Instruments. As I learned at the delightful Bring SwiftUI to Your App workshop, Instruments has a SwiftUI template to measure how many layouts are occurring and how long they take.

You can find the code I used to measure here: https://github.com/jacobvanorder/BooBindings. My procedure is to put all examples in a TabView and then select the tab, present the alert, dismiss the alert, and wait five seconds before I try the next option. Also, I converted all of the timings to microseconds.

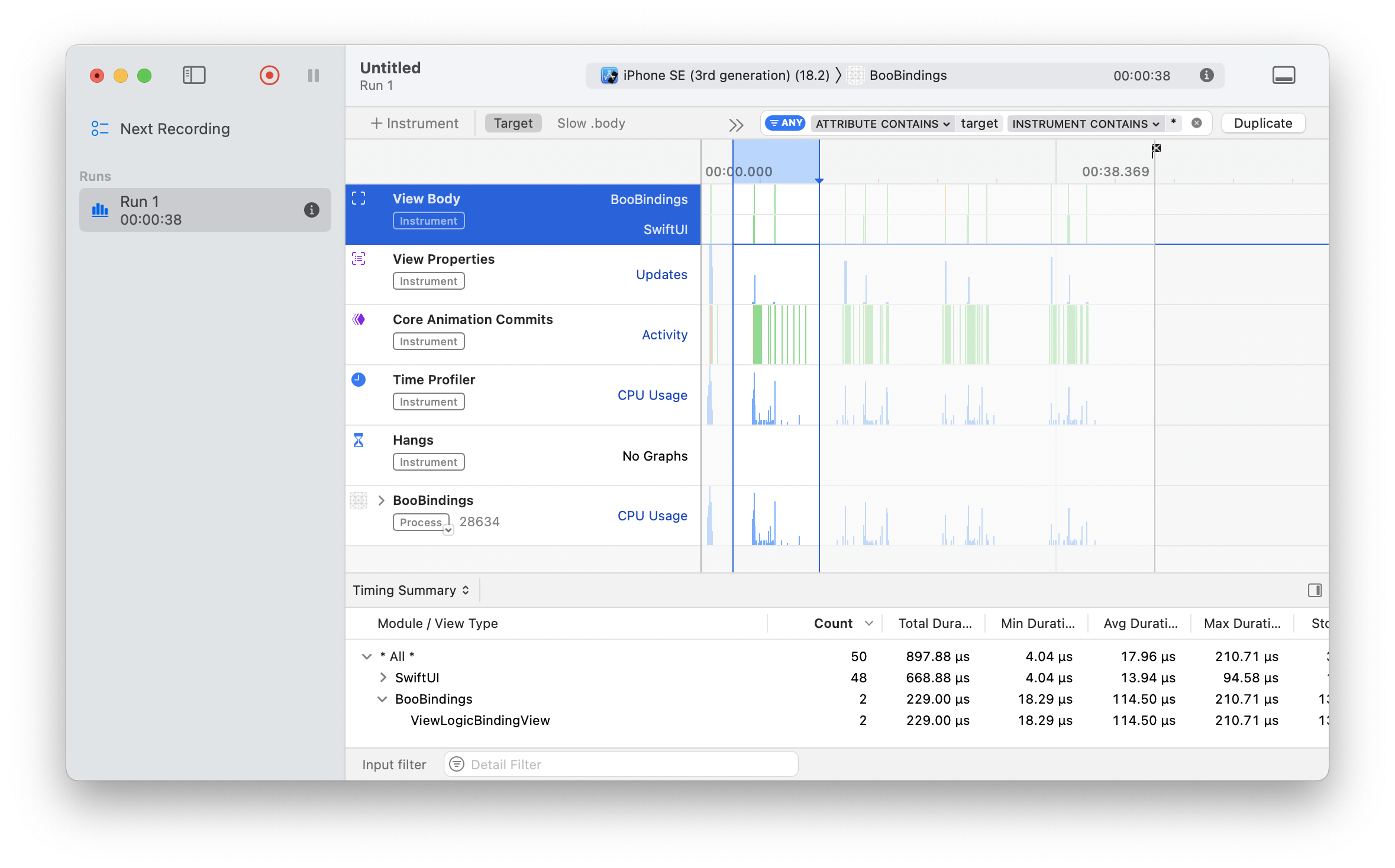

Option Number One: A State Property

In this option, you manually control boolean for showing the alert. Button gets tapped and we set the model object and flip the bool. The alert is driven by a @State bool variable that you’ll have to remember to flip each scenario that happens and will happen if you need to add on in the future.

We have 50 total layouts with a duration of 897.88 microseconds. Two of the layouts are for the ViewLogicBindingView itself.

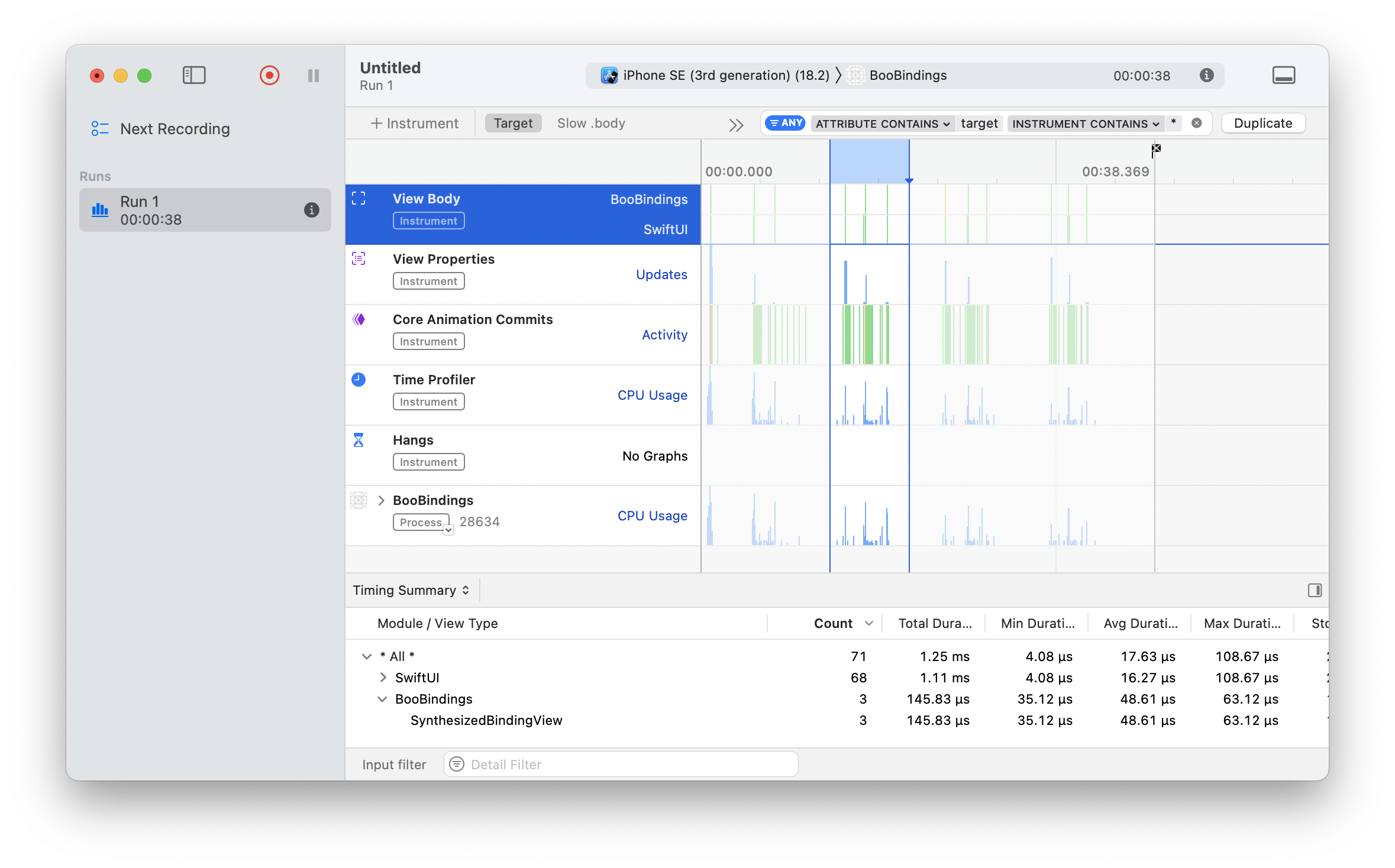

Option Number Two: Synthesized

Here we use the Binding(get:set:) option. No extra @State property and no logic to maintain.

We have 71 total layouts with a duration of 1,250 microseconds. Three of the layouts are for the SynthesizedBindingView itself.

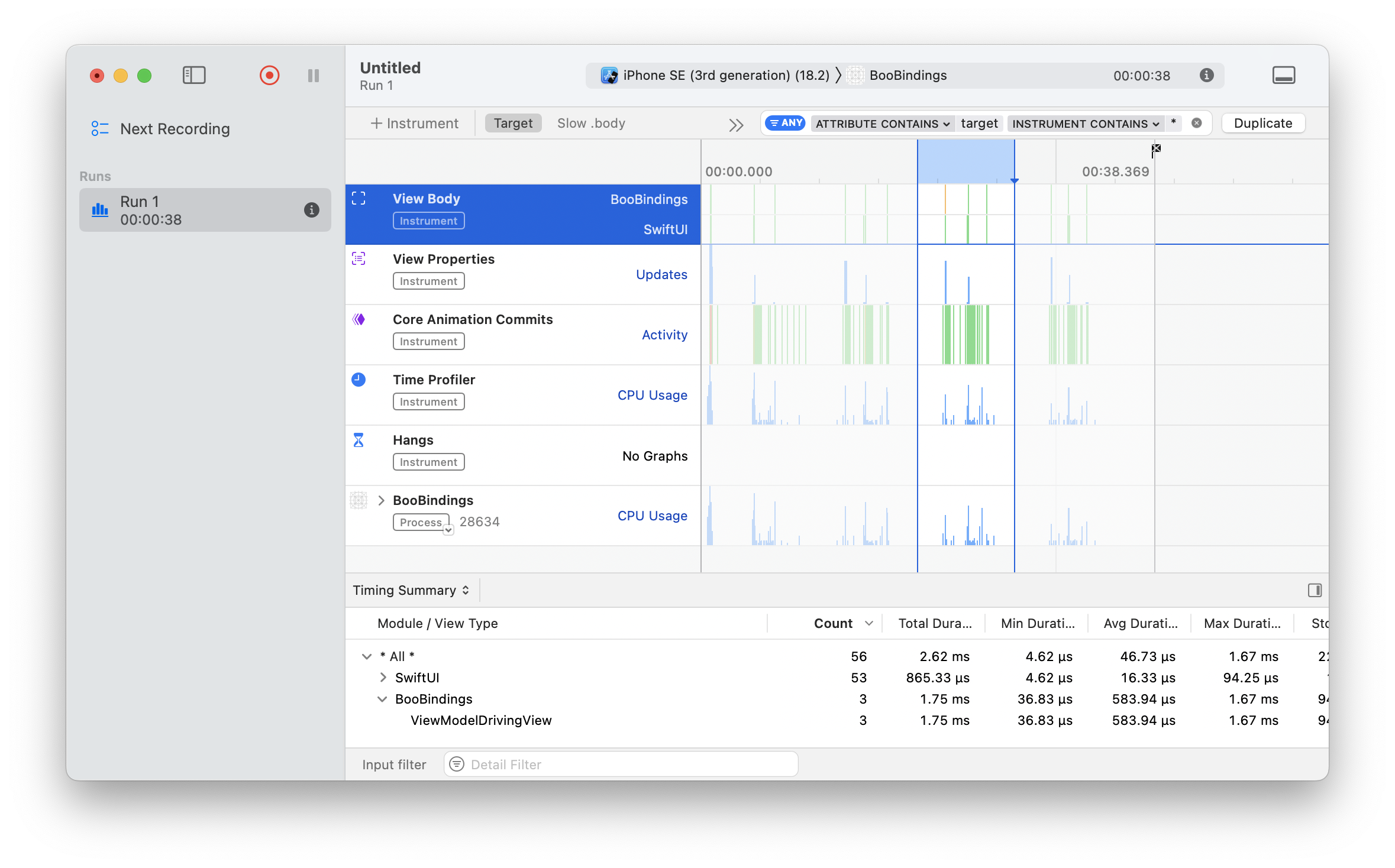

Option Number Three: View Model Driven Option

At the “Bring SwiftUI to Your App” workshop, they also talked about they preferred using @Observable classes when the logic within a view gets unwieldy or difficult to manage. In this case, I create a view model that has both the model object and a var boolean. When the object gets changed, so does the boolean in a willSet on the object. This class is then used as a @State var on the view itself and will trigger a view update when variable change. The plus side to this is that you can unit test this class independently and fairly easily.

We have 56 total layouts with a duration of 2,620 microseconds. Three of the layouts are for the ViewModelDrivingView itself. That is considerably slower, though.

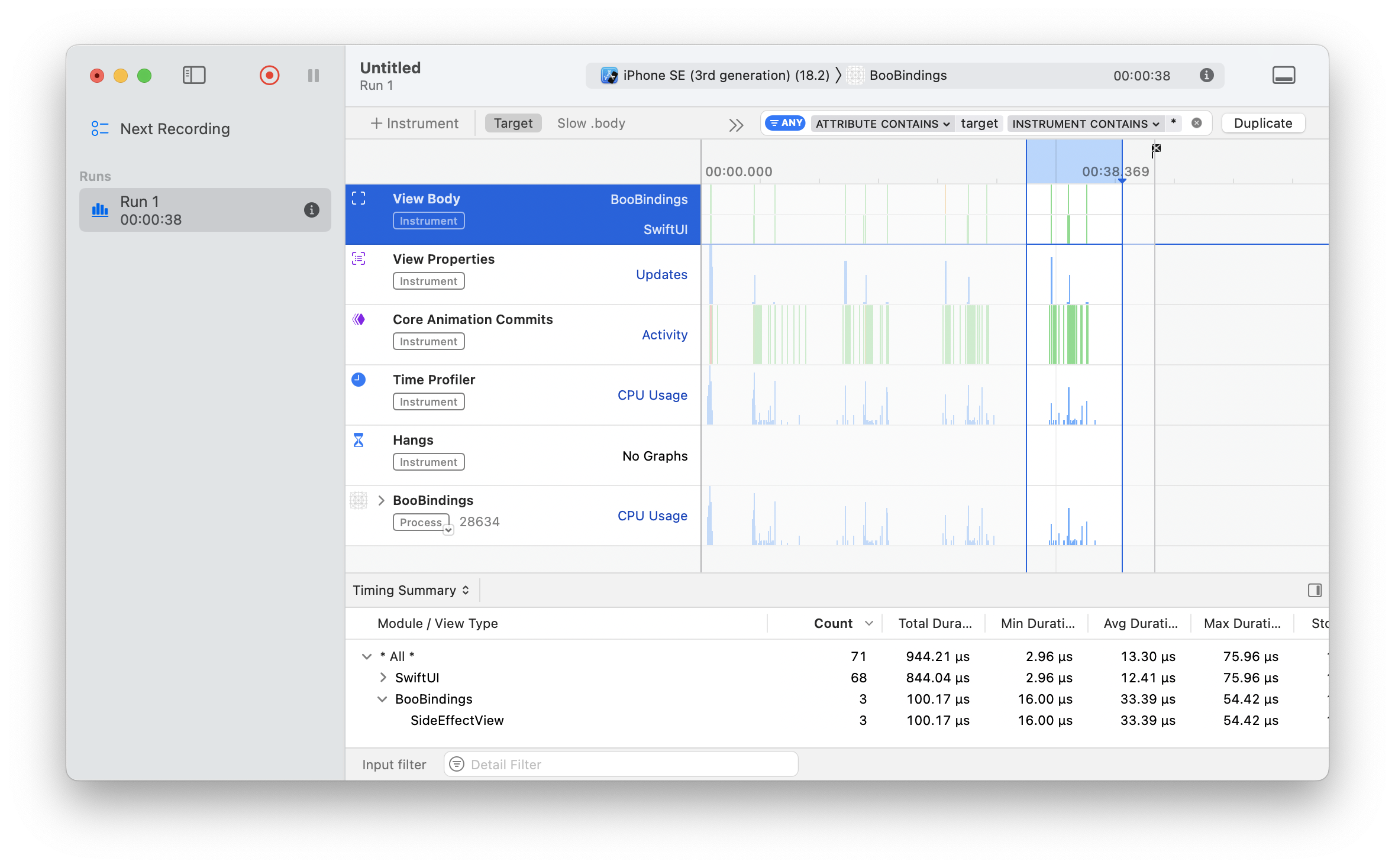

Option Number Four: Side Effect on the View

What if we got rid of the view model but had similar logic on the view where you have both the model object and a var boolean. Again, when the object gets changed, so does the boolean in a willSet. Can’t easily unit test but thems the breaks.

We have 56 total layouts with a duration of 944.21 microseconds. Three of the layouts are for the SideEffectView itself.

In Conclusion

From a purely numbers aspect, the simple solution is the winner and the view model class is the loser but there are other factors to consider. This was the easiest example I could cobble together on a Sunday. Real world apps have complex scenarios that should be unit tested and are maintained by teams of people with varying skill levels.

The real answer to whether you should use Binding(get:set:) is to consider the trade offs of doing so. Run it through instruments and then consider whether the logic you’re introducing is easily testable and maintainable.